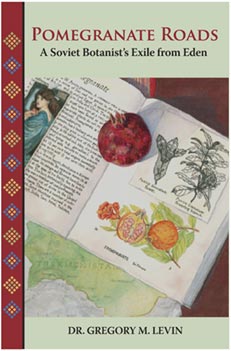

Pomegranate Roads: A Soviet Botanist's Exile from Eden

by Dr. Gregory Levin

For more than forty years, Dr. Gregory Levin trekked across Central Asia

and the Trans-Caucasus in search of rare, endangered and mysterious wild

pomegranates. His home was a remote Soviet station in the mountains that

separate Turkmenistan from Iran. After the break-up of the Soviet Union,

he found himself exiled from his own hidden Eden and his collection of

1,117 pomegranates.

Gregory Levin has written a fascinating memoir of his life with pomegranates. He illuminates the botany, the history and myths, the astonishing range of tastes, and the health benefits—from folklore to

pharmaceuticals—that make it the wonder fruit of our time.

Preview a Chapter from the Book

View Images from Pomegranate Roads

From the Introduction by Editor Barbara L. Baer:

I wish I could explain why I got caught up searching for Dr. Gregory Levin and the wild pomegranates. My quest and failure to find either of them is the background story to Pomegranate Roads.

In the summer of 2001, while driving home on back roads in northern California, I heard words in Russian on Public Radio’s BBC/The World. Anne-Marie Rueff, “The Savvy Traveler,” was broadcasting from rural Turkmenistan, near Iran’s northern border. “The birthplace of the pomegranate was here in the Kopet Dag Mountains of Central Asia. And here is one of the last places on earth where wild pomegranates grow.”

Sonorous languages rose over the sounds of rustling leaves and cries of birds. I heard voices in Russian, English and Italian marveling at grapevines a dozen feet above their heads, at pungent arugula lying at their feet. “Wild pomegranates stretch their canopies along a riverbed,” Anne-Marie said. This was Eden, a threatened Eden. The Russian speaker, a botanist named G. M. Levin, came back to the microphone. He said that conditions were going from bad to worse. “Here in wild pomegranate forests, sheep and cattle are grazing on grasses, eroding land, harming young trees.” The persimmons, pears, apricots, apples, figs, and native grapes and his unmatched pomegranate collection—1,117 different varieties of pomegranates—at the nearby agricultural station of Garrigala were dying from drought because the workers lacked pumps to bring up water from the Sumbar River. “We often carry water cans to each tree,” Levin said.

I felt my throat constrict with thirst as I imagined Levin tending his parched orchards. In my mind’s eye, he was a scientist from a Chekhov story, with a small beard and round glinting glasses. I supposed that he knew personally all the 1,117 pomegranates he had collected from twenty-seven countries on four continents.

Garrigala, the interviewer said, needed financial help. Since the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991, Moscow had cut off funds to its former republics. From the Arctic seas to the Pacific Ocean, Soviet scientists had lost their labs, facilities and salaries—they were left out in the cold. To survive, many put their services up for sale. The need to re-employ nuclear specialists was obvious, but a pomegranate botanist less so.

Levin confessed that he was losing heart and ready to leave the station, but he lacked a successor and feared the collections would perish. Only help from the outside world could save Garrigala.

After the program ended, the fruit still glowed like rubies in my mind. I felt that more than chance had carried Levin’s voice from Turkmenistan to my car radio. This man had been delivering a personal plea, an invitation for me to visit the wild pomegranates and do something to bring their plight to others’ attention.

...Continued

Order your copy

|